Healthcare Venture Investing: Part 1 - Scientific Diligence

Originally published here

When I was trying to get into the venture business, there were many resources that were available that spoke about the world of venture capital. There are loads of books, podcasts and articles about how to pitch, advice from the most successful entrepreneurs and why investors enjoy venture. However, I was noticing that when people talk about the venture capital industry online, it’s almost always related to tech. Additionally, because tech companies are mostly revenue-generating, it’s easier to value them utilizing different financial models. However, because biotech and therapeutics companies are all pre-revenue, valuing companies is a little more difficult.

So when I was trying to learn about the healthcare business, I couldn’t find any good resources that could teach me about how healthcare VCs assess different deals. Now, after being in the venture business for almost 2 years with experiences in both Canada and Europe, I decided to write this article in the hopes that you’ll be able to understand a little bit about what we do.

I’ll separate this series into 3 different buckets; (1) Scientific Diligence, (2) IP and Regulatory, and (3) Evaluating Venture Businesses From a Healthcare Perspective. Each section will be split into individual headings with a few key questions and a small blurb about each one. Some of these are specific to biotech/therapeutics companies so I’ll add a little bit more context around these. Whether you’re a seasoned venture capitalist, emerging entrepreneur, or someone who’s just interested in learning more about the ‘black box’ of healthcare VC, I hope you take something out of this.

Full disclosure: these opinions are purely my own and do not represent my firm. Analyzing every company is unique and should be assessed on an individual basis.

Science lies at the heart of everything we do, and although you don’t need to have multiple PhDs to understand this business, you do need to have the ability to learn science quickly. Being able to read papers, understand experiments and be able to become a quasi-expert on a variety of subjects is extremely important. I was trained as a clinician so sometimes, I still have trouble understanding early-stage science. Nonetheless, Google, Pubmed and academic journals like Nature & Lancet are fantastic resources for being able to learn and I can’t overstate enough how helpful these resources are.

It’s hard for me to compare this to evaluating tech businesses because although you have code underlying every single tech company, I have a sense that evaluating those types of deals is different depending on the type of opportunity. Biotech is a little bit different because although each company has a unique take on tackling a distinctive unmet need, the sciences like biology and chemistry still lie at the heart of it.

This section aims to shine a light on some of the most important concepts we pay attention to from a scientific perspective.

Before I dive in, it’s important for non-healthcare people to understand: what is a platform?

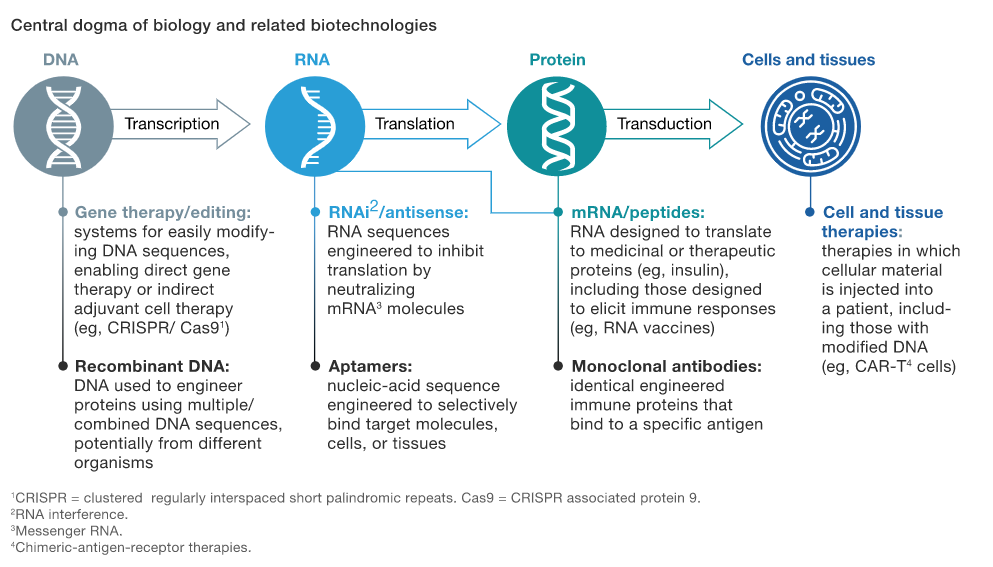

Similar to a technological platform, it’s a back-end service that companies can develop, usually originating out of universities, that step in at different points of the information chain (referred to as ‘the central dogma of biology’) to modify biological processes in the body at the source of various diseases (see exhibit below). In some respects, they have a software-like nature, that allows for the design of multiple new treatments from a single platform. Biotech companies build the platform and design a set of experiments to demonstrate the viability of the platform as a creation machine for new treatments.

If you read the above paragraph and still are unsure of what it is, I’ll try and provide a few examples to illustrate what I mean.

One company that’s been in the news recently is Moderna, which is developing an mRNA vaccine against COVID-19, similar to the vaccine from Pfizer/BioNTech which demonstrated 90% effectiveness in preventing COVID-19. They have an RNA discovery platform that helped them in their ability to rapidly test and advance a vaccine candidate against SARS-COV-2. Their website (see here) does a great job of explaining mRNA and how their platform works, but basically they’re able to discover new mRNA medicines that could be useful in a variety of conditions in infectious disease, oncology and rare diseases. Looking at the picture above, they’re targeting the RNA/translation component of the information chain and this ability to generate numerous candidates in a variety of diseases has propelled them to a market cap north of $28B.

Another example of a platform company is a Canadian company called Abcellera based out of Vancouver. Many Canadians have probably heard this name in the news as they’ve been one of the first companies, in partnership with Eli Lilly, to advance antibody candidates against the Covid-19 virus and received $175M from the Canadian government to build a manufacturing facility in Canada. They’ve recently received emergency use authorization from the US FDA as a treatment for Covid-19. What they’ve been able to successfully do is find novel therapeutic antibodies from a variety of sources in a timely and cost-effective manner, which has propelled them to partnerships with numerous pharma companies, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the United States government. This antibody discovery platform is distinct from Moderna’s as they’re discovering a different type of therapeutic. However, because they’re able to generate multiple different therapies from the same discovery platform, this can provide a lot of value for their partners.

How does the platform work specifically?

How is it unique from what other companies are doing?

Can you address multiple unmet needs via its platform?

This is one of the key things we look at especially because healthcare VCs are growing increasingly interested in platform vs. single-asset companies. As an aside, assets refer to a specific molecule that has IP protection, which are often licensed to big pharma or biotech companies to further develop through commercialization. (For further understanding of biotech business models, please see here)

The healthcare venture business is a tough market because valuations are based on hitting positive milestones, including clinical trial results, and there’s a lot of risk in putting all your eggs in a single basket. That’s why you’re seeing platform companies have higher valuations when they hit the public markets (numerous examples but Moderna is a good one). Because you have a multitude of programs in the pipeline as well as a platform that is unique and differentiated, you have many more ‘shots on goal’ and better chances at getting a successful drug to market.

Having a platform that is unique to your competition and can address multiple unmet needs is extremely advantageous, but it can’t be the only secret sauce the company has. There are a lot of firms that are becoming service companies for pharma and although this business model can be sustainable, it doesn’t produce significant increases in valuation that are tied to owning a drug product. And this is where the drug product itself comes in…

For context, molecules refer to the specific drug product that is being developed. For example, when you take Tylenol, the molecule being referred to is acetaminophen, which has a very specific chemical conformation that interacts with a large number of cells in your body. These molecules often take years to develop with many different iterations being trialed before the final product.

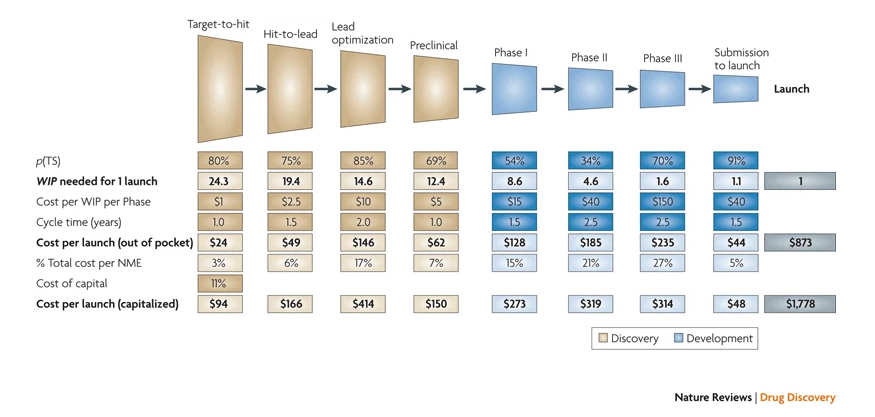

It’s important to state that some prior knowledge of the drug discovery and drug development process is needed in order to really understand this section. You can spend an entire master's degree focused on this subject (I almost did), but this resource here is probably the best one I’ve seen that explains the whole process in a way that makes sense to a layperson. It’s pretty detailed and goes into the costs of each stage, but nonetheless a fantastic resource for understanding the typical drug development process (see here).

What is the molecule (antibody vs. small molecule)?

Do they have the crystal structure/compound made already?

What is the half-life/PK of the compound? Safety data? Biodistribution?

What is the selectivity of the molecule to the target? Are there any off-target effects?

Have you been in touch with manufacturers to look at the scalability of the product?

This is much more specific to biotech/therapeutics development. Once we know you’re developing a drug product, it becomes all about what stage you’re at in terms of development as this helps guide the types of questions you’ll ask and gives us a good background when analyzing the data.

How far along are you in the drug development process? Have you created the drug product and been able to reproduce it in reasonable quantities? Have you filed and been granted IP around it? If so, have you finished in vitro and in vivo experiments? What did the results look like? Did you do any comparable trials to drugs that are already on the market to show sufficient differentiation, whether it be efficacy/safety/etc.? How many safety/toxicology experiments have you done up till now (mouse, non-human primate, etc.)?

For an overview of the different stages and costs associated with drug development, please see below.

There’s a lot to dive in terms of the preclinical development plan but the major questions we look at for preclinical companies are what data have you generated up till now and what are the next major milestones you need to achieve before you can file your drug for IND.

A drug target is a molecule in the body, usually a protein, that is intrinsically associated with a particular disease process and that could be addressed by a drug to produce a desired therapeutic effect.

What is the expression profile of the target?

Is it only selective for the indication (i.e. if it’s a cancer target, is it specific to cancer cells or is it expressed on healthy cells as well?)

Translational data to patients: how upregulated is the target?

With targets that are known and are deemed ‘undruggable’ by current therapies, are you doing anything that is different from what has been tried? What have your results looked like? Do you have extraordinary efficacy/safety data?

For novel targets, it becomes a bit more difficult because there’s extra biology risk. Because the target has not been widely studied and verified by the scientific community, we spend much more time on our diligence looking at why going after that target is unique. How many papers have been published with that target for the given indication? What does the literature say about the target and its expression in the given indication? Is the target expressed only on the diseased cells or is it just up-regulated but expressed on healthy cells as well? What delivery system are you using to ensure specific targeting to reduce the chance of off-target effects?

Off-target toxicities are one of the big reasons drugs fail to advance through clinical trials so this is a major point of emphasis when we’re doing diligence on novel therapeutics.

There are some additional points we focus on during the scientific diligence, but oftentimes if you’re comfortable with the answers through this stage, you’ll bring on additional resources like experts or consultants to give their perspective. As a healthcare VC, there’s only so much you can know and one of the key things I’ve learned in my young career is you have to know your limits. People spend their entire lives focusing on specific targets or disease areas and if you can find the best people to come in and help you, you’d be foolish not to.

This post is Part I of a three-part series.

Stay tuned for the next article which talks about IP and Regulatory.